'Coca is a way of life'

He's tackling poverty and corruption, he's the first ever indigenous Bolivian president - and then there's that jumper. No wonder they adore him at home. But elsewhere Evo Morales is not so popular because of his refusal to cut down on the production of coca, the raw material for making cocaine. ... "The fight for coca symbolises our fight for freedom," he yells. "Coca growers will continue to grow coca. There will never be zero coca." ... a couple of years ago, their crops - the raw material, of course, in the production of cocaine - were faced with eradication under a zero-tolerance policy intended to mollify the United States. ... This is the man who meets world leaders dressed in jeans and a stripy jumper, the man who has outlawed corruption in a traditionally corrupt society, the president who halved his salary on taking office so he could employ more teachers.

This is the man who meets world leaders dressed in jeans and a stripy jumper, the man who has outlawed corruption in a traditionally corrupt society, the president who halved his salary on taking office so he could employ more teachers.

Morales has put Bolivia on the map. His inauguration two weeks ago has electrified Latin American politics; he is, after all, the first indigenous Bolivian - an Aymara - to hold the highest office in the land. Morales has promised to channel more of the proceeds of Bolivia's vast oil and gas reserves to his poorest people, the poorest in all South America. And he has already taken significant steps to eradicate discrimination and exploitation.

Foreign diplomats in the capital, La Paz, admit he is that rarest of things - an honest, incorruptible politician with an urgent desire to improve the lot of his people. There is just one fly in the ointment: the coca. ... in the UK, his election has generated public interest in Bolivian politics for the first time (to say nothing - yet - of astonishment at the appointment of a coca union leader as president) and he wastes no time laying into British imperialism. "Of course it has," ... "The British have always had this policy of invasion and elimination. Certainly they are going to be fascinated by what is happening here."

Bolivia, a landlocked country, is bordered by Brazil in the north and east, Paraguay and Argentina to the south, and Chile and Peru to the west. Two-thirds of its almost nine million inhabitants are indigenous Amerindian Aymara and Quechua, approximately 1% are African descendants of slaves brought over for mining, and the remainder are descendants of European settlers, primarily Spanish.

The conquistadores arrived early in the 16th century and extracted metal resources, mostly silver and tin, for all they were worth, ruthlessly exploiting the indigenous population and creating in the minds of most Bolivians a terrible suspicion of foreign exploitation of natural resources. The conquistadores and their mixed descendants, the minority mestizo, had clung to power for 500 years until Morales's victory in December. He was installed as president on January 22.

Immediately, there was consternation in the northern hemisphere, especially in Washington. Morales's party, MAS (Movement Towards Socialism), a loose conglomeration of leftist unions and social interest groups, had campaigned on a ticket of decriminalisation of coca cultivation and nationalisation of natural resources. What, outsiders wondered, would this mean for the US's war on drugs? What, too, would it mean for international mining, oil and gas companies that had ploughed billions of dollars into exploration and extraction? British companies alone, such as BP, Shell and British Gas had spent upwards of $800m (£459m) on Bolivian projects in recent years. And the US has been spending an average of $150m a year on coca eradication.

Morales said he would be a "nightmare" for the US. He immediately embarked on a tour of world leaders in Europe, China and South America. And during visits to his leftwing political heroes, Cuba's Fidel Castro and Venezuela's Hugo Chavez, he poked fun at George Bush, announcing that he and his friends were the new "Axis of Good".

Morales demonstrated immediately that he was his own man, although at least one overt act of individuality - the wearing of that striped jumper at meetings with King Juan Carlos of Spain, President Thabo Mbeki of South Africa and President Hu Jintao of China - was an accident. "I was literally walking out of the door to begin the tour when I remembered it was winter in Europe," he grins. "I couldn't find my favourite jumper so I grabbed the one that everyone is now talking about. I had no idea it would cause such a fuss."

It is too early to say exactly what Morales and MAS will do. He appointed his cabinet only last week but already alarm bells have begun to ring; the minister responsible for the economy is Carlos Villegas, a leftwing academic from the San Andrés University in La Paz. And the person in charge of fighting narco-trafficking? Felipe Caceres, a coca growers' union leader. Is this, then, the dawn of the world's first narco state? Morales says it is not. ... to talk about his roots, his influences and why we should try to be more understanding about his support for coca.

"You have to realise that, for us, the coca leaf is not cocaine and as such growing coca is not narco-trafficking," he says. "Neither is chewing coca nor making products from it that are separate from narcotics. The coca leaf has had an important role to play in our culture for thousands of years. It is used in many rituals. If, for example, you want to ask someone to marry you, you carry a coca leaf to them. It plays an important role in many aspects of life."

Unlike other coca-producing countries, such as Colombia, there is here a genuine history and tradition associated with coca use. To the Amerindians, Mama Coca is the daughter of Pachamama, the earth mother. "Before you go to work, especially in agriculture, you will chew some coca leaf," Morales continues. "After lunch, after a nap, you might have some. If you drive long distances for your work, you will chew it to help you stay awake. During the night, you will see police officers on patrol with their cheeks full of coca leaves.

"It is used as tea to combat altitude sickness and made into herbal remedies, including cough mixtures, for a variety of ailments. In the past, popes have used it, kings of Spain, Fidel Castro. In your culture, you might have a cocktail or a glass of wine when we would chew some coca. During the republican era, miners used coca to work harder to send more tin to the US.

"For us, it is a way of life, but coca is not cocaine. Traditionally, Bolivians have not processed it into the narcotic drug cocaine. We completely oppose that. I am saying no to zero coca, but yes to zero cocaine." ... people in the west, or developed northern hemisphere countries, know little or nothing about the Amerindian tradition of coca use. When you arrive in your hotel in La Paz, at an altitude of more than 4,000m, there is an urn of coca tea in the lobby, made from teabags that look exactly like your Darjeeling breakfast brew, to help combat altitude sickness. ... And everywhere, almost everyone chews the leaf. But, as Morales explains, this is not the heavy narcotic substance derived by soaking the leaf in kerosene and processing with sulphuric acid.

When you do begin to understand its uses, ... Yes, there is habitual "innocent" and traditional use of the leaf here, but there is also production on levels vastly exceeding what is needed for such uses. And this is used to make cocaine. There is legal production in two areas, the Yungas, to the north of La Paz, and the Chapare, to the east. Cocaleros are allowed to farm 12,000 hectares in the Yungas and 3,200 hectares in the Chapare. But, in reality, much, much more is grown.  ... Unofficially, the US estimates that only 5,000 hectares is needed to satisfy the demands of traditional usage. The UN says 36,300 tonnes of coca leaf was produced in 2004 - of which it estimated that 25,000 tonnes was available for cocaine production. It takes between 300 and 500kg of coca leaf to make 1kg of cocaine.

... Unofficially, the US estimates that only 5,000 hectares is needed to satisfy the demands of traditional usage. The UN says 36,300 tonnes of coca leaf was produced in 2004 - of which it estimated that 25,000 tonnes was available for cocaine production. It takes between 300 and 500kg of coca leaf to make 1kg of cocaine.

Morales flatly refuses to admit it, but without narco-trafficking, large sections of his community would simply starve. Some estimates say that at any given time, one-third of the population relies directly or indirectly on the coca industry. At the Adepcoca market in Villa Fatima, La Paz, the largest coca market in Bolivia, thousands of poor campesinos arrive, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to weigh and sell their coca. ... The buyers are registered and all the coca they buy is supposed to be used for chewing or tea. Coca leaves are everywhere, smelling of day-old cut grass on a summer compost heap. ...

One of those who has come to sell his coca ... He farms three legal catos - 40m x 40m plots - and has brought 20 taquis, for each of which he expects to earn 750 Bolivian dollars ($94). In the Yungas, there are three harvests a year; in tropical Chapare, there are four. ... "I have two children and, for me, it means we have food, I can pay for my children's education and bring them up properly. If it was left up to the Americans, all the crops would be eradicated and we would starve. We would have no way to make an income." Asked how he would feel if the buyer of his crop channelled it into illegal cocaine production, he replies: "I wouldn't know anything about that." ...

This is Morales's stronghold, where he rose to prominence as a coca union leader. It is also where, according to La Fuerza Especial de Lucha Contra el Narcotráfico (FELCN), the military force that combats narco-trafficking, 80% of all the maceration pits, in which leaves are soaked and turned into cocaine paste, are found during eradication patrols. ...

The average cocalero is poor and knows little about cocaine. These are the people whose plight Morales wants us to understand. Efrosina says her land is poor, but even a fertile cato will bring in only $450 every few months. At street prices in the UK, that would be the cost of approximately five grammes of cocaine. The adults are wearing repaired clothes, the children have little in the way of a future outside coca growing. "I used to farm 12 catos but only one was legal," Efrosina says. "Then, in 2004, the FELCN came and tore up the illegal plots. They asked me which one I wanted to keep and I told them. Then they tore that one up and left me with an infertile cato.

"I used to farm 12 catos but only one was legal," Efrosina says. "Then, in 2004, the FELCN came and tore up the illegal plots. They asked me which one I wanted to keep and I told them. Then they tore that one up and left me with an infertile cato.

"It would help if we could grow more coca legally. We are all opposed to cocaine, but coca could be used in other things - medicine, teas, pomades, creams. Without growing coca, my family would starve."

Evo Morales was born in 1959 in the village of Isallavi in the department of Oruro on the high southern Altiplano east of the Chilean border. He was one of seven children, but four died within a year of birth. "That is normal among the poor," he says. "If you want a family in Bolivia, be prepared to have nine or 10 children so you will have some left."

There was no electricity or potable water and, like so many in that region, droughts and economic depression forced Morales's family to move to cities or to the more fertile Chapare region. His father, Dionicio Morales Choque, and mother, Maria Ayma Mamani, both now dead, worked in agriculture.

Morales recalls: "They were illiterate. When I first went to school in the city, the other children would laugh at me and call me ugly because I was Aymara. If I spoke my language, they would laugh and know I was Indian, and at that time I didn't speak Spanish, so to avoid being laughed at, for a long time I didn't speak at all.

"There was much discrimination towards the indigenous population. During the time of my grandmother, only 80 or 90 years ago, there were cases of Aymara who learned to read having their eyes taken out. Some who learned to write had their fingers chopped off. When my grandmother and her friends were finally allowed to go to school, they were repeatedly held back and never allowed to graduate." ...

Morales's political career began in 1981 when he was appointed secretary of sports in the coca union of San Francisco in Chapare. From there - he had already worked briefly as a llama herder and completed a period of military service - he rose through the union ranks and, in 1992, was elected to the presidency of the six coca union federations of the Chapare.

In 1997, he was voted as a deputy to the Bolivian congress and became a constant thorn in the side of successive governments more prepared to pander to the US than he was. In 2002, he was thrown out of congress amid allegations that he had participated in the murders of three police officers during civil strife over coca production.

A popular uprising prevented him from being imprisoned and today the charges are widely considered to have been trumped up with the collusion of the US. "I have been accused of being a narco-trafficker, an assassin, a terrorist and a member of the coca mafia," he says. "The Americans say that I have received money from the Farc [the paramilitaries controlling cocaine production in Colombia], from Cuba and Venezuela. None of this is true.

"I have been hated, mistreated, humiliated and thrown into prison three times for trying to defend my people. But now we are in government and I want to bring peace and justice for all. There is no room for revenge. We want to make being Bolivian inclusive for all. There will be no exploitation or discrimination of anyone."

In December's election, he replaced the incumbent President Carlos Mesa with 54% of the vote in an eight-horse race. That gives him an unprecedented mandate and a strong hand in renegotiating oil and gas contracts with outside investors. His definition of "nationalisation" is somewhat loose and he promises that foreign companies have nothing to fear - he will, he says, respect property rights. And he will have to cooperate with the huge hydrocarbon companies if Bolivians are to benefit from the extraction of gas reserves worth a potential $250bn.

"We obviously need investment," he says. "We need investment from states and also from private business. But they will be our associates, not our bosses. On other investment, such as tourism, people are welcome to invest in Bolivia in any manner they please. My government will guarantee that all who invest, public or private investors - but preferably public - will receive our full cooperation."

Which brings us back, inevitably, to the coca. He won't say whether there will be more or less production under his government, simply that there will be neither unbridled cultivation nor eradication. Figures, he says, will be set by the government in consultation with the unions.

"I want to industrialise the production of coca and we will be asking the United Nations to remove coca leaf as a banned substance for export," he says. "That way, we can create markets in legal products such as tea, medicines and herbal treatments. There has even been research in Germany which shows that toothpaste made from coca is good for the teeth. That will then enable us to be tougher on the narco-traffickers. As I said, no to zero coca, yes to zero cocaine."...

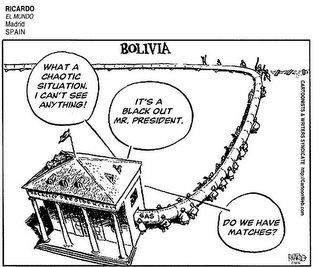

Morales holds deep and honest convictions that will simply not allow millions of poor cocaleros to be hung out to dry by anti-drug policies that would reduce much of his population to utter poverty. He has the potential to be a great president for the poorest nation in South America. Whether he can carry the more extreme elements of his MAS party with him remains to be seen. One thing is certain; he will need time if he is to succeed, and time is not something normally afforded to Bolivian presidents. In the 182 years since it was granted independence from Spain, this chaotic and crippled country has welcomed and waved goodbye to more than 190 failed governments.

source

Bolivia's Morales pressured to increase coca crops

Coca leaf is stripped from a sturdy bush that grows like weed and needs little care. In its traditional use, dating back to 2,500 years BC, coca leaves are chewed and held in a wad in the cheek as a mild stimulant.

Alternative uses of coca leaf range from coca tea and soft drinks to toothpaste, face creams and even a natural version of the potency-enhancing drug Viagra.

With thousands of hectares under cultivation elsewhere, Bolivia ranks as the world's third-largest cocaine producer. But the growers here insist they have nothing to do with the drugs trade. "What we need is an end to the Satanisation of coca growers. We are not drug traffickers, we are not criminals," said Leonilda Zurita, head of the women's federation and a close confidante of Morales.

"What we need is an end to the Satanisation of coca growers. We are not drug traffickers, we are not criminals," said Leonilda Zurita, head of the women's federation and a close confidante of Morales.

Her battle cry during the election campaign, in her native Quechua, was "kausachum coca, wainuchum yankees" -- long live coca, death to the Yankees.

source

Bolivia minister wants coca fed to school children Bolivia's foreign minister says coca leaves, the raw material for cocaine, are so nutritious they should be included on school breakfast menus.

Bolivia's foreign minister says coca leaves, the raw material for cocaine, are so nutritious they should be included on school breakfast menus.

"Coca has more calcium than milk. It should be part of the school breakfast," Foreign Minister David Choquehuanca was quoted as saying in Friday's edition of La Razon. ...

A coca leaf weighing 100 grams contains 18.9 calories of protein, 45.8 mg of iron, 1540 mg of calcium and vitamins A, B1, B2, E and C, which is more than most nuts, according to a 1975 study by a group of Harvard University professors.

source

Friday, February 10, 2006

bolivia, evo morales and hope

Posted by audacious at 10.2.06

Subscribe to:

Post Comments

(Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment