LAW-U.S.-SADDAM TRIAL

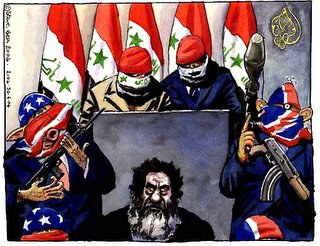

U.S. blasts international community for failing to help with Saddam trial

WASHINGTON, Feb 15 (KUNA) -- As is evident by the trial of former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, the international community "has essentially turned its back on justice and accountability in Iraq," State Department legal adviser John Bellinger said on Wednesday. The Iraqis have asked for international support for the tribunals, "and unfortunately, the international community has not come forward in that regard, " Bellinger said during a Foreign Press Center briefing.

The Iraqis have asked for international support for the tribunals, "and unfortunately, the international community has not come forward in that regard, " Bellinger said during a Foreign Press Center briefing.

The Iraqi Special Tribunal originally mandated that there be international advisers to the court, "and very, very few countries came forward," he said. In fact, "the Iraqis have had to amend the statute" so that they are now no longer required, but simply "may be provided," he added. ...

"Before the Iraq war there was, in fact, a consensus that the human rights situation in Iraq was among the worst the world had seen since World War II," he said. "The human rights organizations, the UN, the international community had roundly condemned Saddam for his atrocities and had called, in fact, for the world to do something about it." But unfortunately, "now, after the Iraq war, the international community has essentially turned its back on justice and accountability in Iraq," Bellinger said. ...

source

Even Saddam must be given a chance

Despite circus, guilt can't be presumed

Steven Edwards, National Post

February 15, 2006

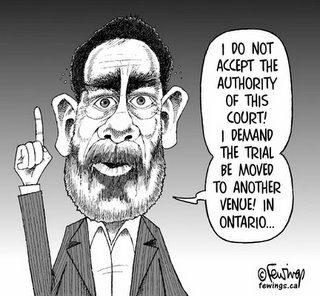

NEW YORK - The trial of Saddam Hussein plumbed new depths of farce yesterday as the former Iraqi dictator announced that he and his seven co-accused were in their third day of a hunger strike to protest their treatment. It doesn't take an international jurist to know that assigning culpability for the crimes against humanity committed under Saddam's rule was always going to be messy. Which makes some say getting the show completed as quickly as possible, followed by a swift execution, might have been the best approach.

It doesn't take an international jurist to know that assigning culpability for the crimes against humanity committed under Saddam's rule was always going to be messy. Which makes some say getting the show completed as quickly as possible, followed by a swift execution, might have been the best approach.

Almost certainly that would have been the position of Winston Churchill, the British Second World War prime minister, who wanted Nazi leaders summarily executed without trial and Hitler placed in the electric chair if captured. ... Still others say rendering justice has to afford the accused a genuine presumption of innocence unless proven guilty, and that means there has to be a chance he or she will walk free.

Churchill's solution -- at face value extreme for due process believers -- makes sense to the extent nothing can occur under a dictatorship without the regime's knowledge. Hence, prosecuting regime members as suspected criminals, where doubt of guilt may exist, is illogical.

"A dictator is responsible for all the crimes committed under his regime," says Yaron Brook, executive director of the Ayn Rand Institute, which adheres to the late philosopher's objectivism. "It might be valuable to have some kind of a tribunal where the evidence is presented, but ... the trial is [not] there to prove him guilty. ... Paying the price of doing otherwise are the daily victims of attacks against coalition forces and Iraqi civilians, argues Brook. A central goal of the war is also lost.

"The purpose was to get rid of the Saddam regime, with all its elements, including its propaganda," Brook says. "Yet here we are keeping it alive, and we're keeping the insurgency alive because [among insurgents] there is still hope Saddam could again be president if the trial went their way or if they kill enough of the judges." ...

Some have argued Saddam should have been tried in an international war crimes court, but Rabkin, an opponent of international justice systems, said ad hoc UN-backed courts have proceeded no quicker in many of their cases. "We do know that Saddam has studied the Milosevic trial," he said, referring to the trial in The Hague of former Yugoslav strongman Slobodan Milosevic, whose harangues have become legend amid proceedings that began in February, 2002.

"We do know that Saddam has studied the Milosevic trial," he said, referring to the trial in The Hague of former Yugoslav strongman Slobodan Milosevic, whose harangues have become legend amid proceedings that began in February, 2002.

In Western national systems, judges first look to the lawyers to persuade their clients to remain orderly, while presumption of innocence dictates that defendants cannot be shackled or dressed in prison garb in front of a jury.

"If it appears clear to be the strategy of the defence team to disrupt, which has been the case in political trials, that usually suggests an institutional problem," says Tiphaine Dickson, a Quebec defence attorney specialized in international criminal law.

"It's fair to say that these defendants are overwhelmingly considered guilty. But when guilt is presumed the most fundamental tenet of justice is violated, as is the notion of fairness itself."

source

Thursday, February 16, 2006

saddam, justice violated?

Posted by audacious at 16.2.06

Subscribe to:

Post Comments

(Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment