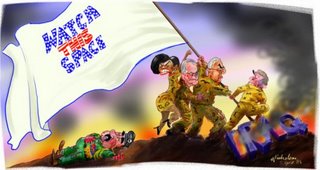

Democracy: Iraq votes, Bush vetoes

Ehsan Ahrari, Mar 31, 2006, Asia Times Call it desperation, but the United States has started to take measures in Iraq that would wreck its most cherished goal there: democracy.

Call it desperation, but the United States has started to take measures in Iraq that would wreck its most cherished goal there: democracy.

US Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad is reportedly campaigning to either dump the United Iraqi Alliance's (UIA) candidate for prime minister, Ibrahim al-Jaafari, or force him to withdraw. Khalilzad has taken the drastic measure of appealing to the Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani to that effect.

Parliament's largest bloc nominates the prime minister under Iraq's constitution, and last month Jaafari captured the nomination by one vote with the help of Shi'ite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. However, the 275-member parliament is now at an impasse in talks over forming a new government as the main Kurdish, Sunni Arab and secular blocs staunchly oppose a Jaafari premiership.

If democracy is meant to reflect the will of the people, Jaafari, for all his flaws, is a legitimate candidate to become the country's first permanent prime minister. But US President George W Bush is making it clear that his version of democracy in Iraq means having his preferred candidate at the helm.

There are conflicting reports from Iraq about the mechanism of sending this message to Sistani and about who conveyed it.

The grand ayatollah, the ultimate arbiter of post-Saddam Hussein Iraqi politics, has made a point of not granting meetings with US officials throughout the occupation. It is possible he made an exception for Khalilzad, whose selection to be ambassador of Iraq is not merely fortuitous. The US diplomat is a native of Afghanistan. In that capacity, he is perceived as a Muslim-American by those in Iraq who are impressed by such symbolism.

What is missing from that sort of symbolism is the fact that Khalilzad is also one of the established neo-conservatives (albeit belonging to the second or even third tier) of the Bush administration. In that capacity, he has no problem defining democracy as nothing but the selection of US-preferred leaders. However, the US strategy of handpicking Iraqi and Afghan politicians (it adopted the same strategy in Afghanistan where it gave the nod to President Hamid Karzai) appears to be a measure of last resort.

According to one report, the US government sent a letter on the issue to Sistani. Washington has denied Bush was the signatory. In all likelihood, Khalilzad used one of his own back-door functionaries to send a letter.

According to another source, Khalilzad used a meeting with Abdul Aziz al-Hakim, head of the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI), to deliver the message to Sistani. Considering the sensitive and highly unusual nature of the request, Hakim reportedly refused it at first, but then passed it on.

Why is it that Jaafari has become a lightening rod for so much controversy in Iraq?

The situation in Iraq is edging steadily toward desperation. Apart from being Sadr's candidate, Jaafari is also preferred by Iran. Working against Jaafari is that as interim prime minister, he did not have an impressive record. More to the point, Sunnis perceive him as being unable to raise himself above sectarian politics.

However, such criticism is unfair since Jaafari had to undergo on-the-job training as prime minister. Also, he was learning the ropes while insurgents were trying to blow up Iraq. And, considering that the Sunnis were the chief supporters of those insurgents, he could not have been excessively magnanimous about all issues that were at the heart of their concerns. Finally, Jaafari's candidacy remains controversial because, aside from the Sunnis, Kurds and secular Shi'ites do not like his Islamist credentials.

Iraqi politics allow for no mistakes and treat harshly those who make errors. The more visible politicians are, the harsher judgment they are likely to receive from the public. But the US problem with Jaafari is that he is viewed not only as an Islamist candidate, but also a friend of Sadr and Iran. In that capacity, he remains the source of considerable distrust by the Americans.

The question is whether it is a reasonable strategy to interfere in Iraqi power plays and even go to the extreme of contacting Sistani to sack Jaafari. The answer is, of course not. It only underscores the weakness and desperation of US officials.

If Jaafari is indeed dropped as a result of US maneuvers, the Shi'ite schisms are likely to widen, a development unlikely to help the American desire for a national unity government. The pro-Jaafari forces have already spelled out the essence of what their public position would be if their candidate is replaced. One Jaafari spokesman said: "The US ambassador's position on Jaafari's nomination is negative. They want him [the prime minister] to be under their control."

Since democracy is essentially a numbers game, it will be interesting to see what happens if Jaafari remains and the UIA remains intact. Even though the UIA is a broad coalition of about 20 Shi'ite groups, its two dominant partners are Hakim's SCIRI and Jaafari's Da'wa Party. Looking at the numbers, the survival of the UIA (128 seats) provides stability to Iraq's electoral politics. That stability is sorely needed at this critical stage of its democracy.

However, Khalilzad seems to have concluded that, despite the large size of the UIA compared to other parties, the mere presence of Jaafari at the helm will be highly divisive. The alternative, if Jaafari were dropped, would be splitting up the UIA. That is where, according to the US strategy, SCIRI, not the Da'wa Party, would become the dominant player. Its candidate, Adel Abdel Mahdi, would be selected prime minister.

The US had already let it be known that Mahdi was its preferred candidate even before Jaafari was elected. In the US's post-Jaafari scenario, Mahdi would form a coalition government with the support of SCIRI, the Iraqi Accordance Front (44 seats), the Iraqi National List (25 seats), the National Dialogue Front (11 seats), Kurdistan Coalition (53 seats) and Kurdistan Islamic Union (5 seats).

When based purely on numbers, Khalilzad might not be pursuing a bad strategy. What is sorely missing from this strategy, however, is the fact a breakup of the UIA would also intensify Shi'ite divisions, a development the US can little afford.

So the Bush administration is clearly gambling in its attempts to break up the UIA by insisting Jaafari be dropped. Another unknown is how Iran would react to this development, especially when it is about to start a dialogue with Khalilzad on the future of Iraq.

At the same time, it is also possible Khalilzad's maneuvers to bring about the demise of Jaafari might also be aimed at gaining some negotiating advantage over Iran. Meanwhile, Iran is not oblivious to the implications of Khalilzad's maneuvers, and might make a few strategic moves of its own in coming days.

As these maneuvers and counter-maneuvers are being played out among various Iraqi sectarian and political factions, Iran and the United States, the country's stability continues to deteriorate. It is ironic that, by indulging in these maneuvers, all the power brokers in Iraq seem to be doing the bidding of the country's insurgents who want to ensure Iraq remains unstable.

Monday, April 3, 2006

how voting and democracy works ...

Posted by audacious at 3.4.06

Subscribe to:

Post Comments

(Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment