Pascale Combelles Siegel January 4, 2007

In the wake of last year's controversy over the publication of cartoons of the prophet Mohammed, Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad decided to launch an international cartoon contest. The objective: invite people from all over the world to question the reality of the Holocaust. The contest drew participants from all over the world and yielded more than 200 Holocaust-related cartoons.

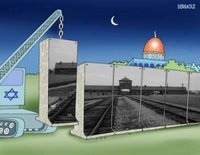

The first prize went to Moroccan cartoonist Abdellah Derkaoui. His caricature features an Israeli crane building a high wall around Jerusalem. In the background, half hidden by the wall, lies the dome of the Al-Aqsa mosque. Painted on the wall is a picture of the entrance to a death camp.

The choice of Derkaoui's cartoon is somewhat surprising. The cartoon does not deny the Holocaust, for it uses the best-known symbol of the Nazi genocide to criticize current Israeli policies toward the Palestinians. This is not denial. The cartoon acknowledges that the Nazi genocide actually took place, that it was wrong, and that it remains an indisputable reality of Middle Eastern politics.

Holocaust Cartoon Contest

Pascale Combelles Siegel January 4, 2007

In the wake of last year's controversy over the publication of cartoons of the prophet Mohammed, Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad decided to launch an international cartoon contest. The objective: invite people from all over the world to question the reality of the Holocaust. The contest drew participants from all over the world and yielded more than 200 Holocaust-related cartoons.

The first prize went to Moroccan cartoonist Abdellah Derkaoui. His caricature features an Israeli crane building a high wall around Jerusalem. In the background, half hidden by the wall, lies the dome of the Al-Aqsa mosque. Painted on the wall is a picture of the entrance to a death camp.

The choice of Derkaoui's cartoon is somewhat surprising. The cartoon does not deny the Holocaust, for it uses the best-known symbol of the Nazi genocide to criticize current Israeli policies toward the Palestinians. This is not denial. The cartoon acknowledges that the Nazi genocide actually took place, that it was wrong, and that it remains an indisputable reality of Middle Eastern politics.

One might have expected much worse from the Iranian government. Since his election, Ahmadinejad has made a number of provocative statements, casting doubt on the awful realities of the genocide and reiterating the old Arab view that if the genocide occurred in Europe, then Europe should have offered the Jews reparation in Europe and not made the Palestinians suffer the consequences of its tragic policies.

However, the Iranian government refrained from choosing one of the rabidly anti-Semitic cartoons that drew on 20th-century European caricatures of Jews. Nor did it choose a cartoon that equated Israeli policies with the Nazis' quest for world domination. Nor did it choose a cartoon depicting Israel and the United States in cahoots to exploit the Palestinians. All these themes were depicted in various entries to the contest. The rejection of these more extreme representations might be a sign of moderation from an Iranian government seeking to change its strategic relationship with the U.S. government.

Of course, Derkaoui's acknowledgement of the Nazis' Holocaust does not represent an ideological epiphany. It is designed to draw a moral equivalence between what happened to the Jews in Europe under Nazi domination and what is happening to the Palestinians at the hands of Israel now.

This moral equivalency is very much debatable. Israel is not engaged in a Nazi-like policy against the Palestinians. Israel has never called for the extermination of Palestinians like the Nazi party toward the Jews in the 1930s. It has never engaged in a genocidal policy against the Palestinians like Germany did with the Jews in the 1940s. The moral equivalency argument also conveniently forgets that Palestinian militants have adopted murderous tactics and that some of the Palestinian political leadership still does not recognize the right of Israel to exist. It also conveniently forgets that the Arab world has committed its share of duplicitous acts of treachery against those same Palestinians.

In short, there is really no moral equivalency between the two situations. But Derkaoui aims not so much to portray history accurately but to shock the West into realizing that Israel's heavy-handed tactics have, for too long, inflicted undue and immoral suffering on the Palestinians. That argument is likely to resonate loud and clear around the Middle East where the Palestinian cause has become the rallying cry and the symbol of the West's injustice toward the Arab-Muslim world.

The success of the contest is based on a deep-seated feeling in Muslim societies that the West practices double standards when it comes to free speech: restraint when it comes to discussing Israel but blasphemy when it comes to discussing Islam. Indeed, all over the Middle East, many feel that issues such as the Holocaust or Israeli policies in the West Bank are not legitimate objects of discussion in the West. Such views are widespread, including among Arab elites.

As for Western audiences, the moral equivalence argument will not likely go over very well. But Derkaoui's cartoon might be an opportunity to open a constructive dialogue on the subject. For such flawed moral equivalencies to become a relic of the past, however, both the national aspirations of the Palestinians and the right of Israel to a secure state have to be successfully addressed. But that will take more than cartoons and dialogue.

0 comments:

Post a Comment