Iraqis face a more brutal life with each passing month

Iraqis face a more brutal life with each passing month

Jonathan Steele in Baghdad, March 31, 2006, The Guardian

Terror and chaos reign, and the titanic challenge of ensuring political stability has barely begun to be addressed.

The pavements outside the American embassy here are peppered with odd concrete structures. They look like oversized kennels, about four feet high and six feet long, with a low wall at each end. Painted on them, large letters explain their purpose - duck and cover.

This is deep inside the well-guarded Green Zone, but if mortar rounds start to fall as you walk or drive by, these pygmy bunkers are where you and up to 10 people can squeeze in and crouch until the coast is clear. Like the iconic image of the last helicopter leaving the roof of the US embassy in Saigon in 1975 with terrified people struggling to clamber aboard, these ugly shelters may eventually achieve similar symbolic status.

For Iraqis in Baghdad, duck and cover is already a metaphor for daily life. On each of the seven visits I have made here since Saddam Hussein was toppled, security conditions have worsened. The downward slide since my previous trip for the December elections seems particularly steep.

The spate of sectarian revenge killings that followed the bombing of the golden-domed shrine at Samarra last month is not yet over, in spite of an 8pm curfew imposed in Baghdad. Abductions and murders continue relentlessly. Bodies, often scarred by torture and with their hands tied, have been turning up on lonely roadsides at a rate of 13 a day. Shops close their metal shutters and streets start emptying at 4pm as people flee home well before the curfew. Many Baghdadis rarely venture out except to the corner store. Those who drive to work vary their routes. A doctor who uses taxis to get to her hospital says she tells the driver she's a patient, "since it makes kidnapping a bit less likely".

Even shopping has become risky. Eight people at an electrical-appliance store in the middle-class suburb of Mansour were lined up against a wall and shot dead this week by masked gunmen. Two money-exchange dealers and three other shops were also attacked by armed raiders in Baghdad. Whether the motives are criminal or political, the result is terror and chaos.

Iraqis who work for the government or have jobs in the Green Zone are especially vulnerable. Soldiers in the national army and policemen usually go home in civilian clothes. Some dare not tell their families, let alone their neighbours, what their jobs are. Throughout Iraq policemen are dying at a rate of 150 a month, yet new recruits never stop coming forward, attracted by the pay in a rock-bottom economy.

Senior civil servants are key targets. Inspector generals have the task of auditing ministries for corruption and other abuses. Two of the 31 have been assassinated, and at a press conference on Tuesday the two who came declined to be filmed. The UN mission is back in Baghdad, working on human-rights, constitutional-reform and rule-of-law issues, but it now shelters in the Green Zone after the catastrophic suicide bombing of its old headquarters in 2003. As a result, contacts with civil society are more difficult and the UN is planning to build a video centre in town so that Iraqis can hold conference calls with officials rather than take the risk of walking into the Green Zone.

While the violence grows, the political deterioration over the past three months is also remarkable. Iraq's elected leaders have failed to agree on who should be the country's next prime minister and president, leaving a vacuum of authority that is making Iraqis increasingly cynical about democracy and eager for a strong hand at the top.

Relations between Iraq's majority Shia community and the Americans are at their lowest point since the fall of Saddam Hussein. The group that stood to gain most from his departure is turning on the US. Leaders of three rival Shia factions united this week to condemn an attack on a mosque complex by Iraqi troops with US support, in which at least 20 people died. The US military claims the raid targeted militias and hostage-takers, but its explanations came late. Denouncing the action as a slaughter of innocent worshippers, senior Iraqis had already taken public positions from which they could not easily retreat.

Already suspicious of last autumn's American "tilt" towards the Sunnis, Shia leaders feel the US is undermining their election victory by interfering in the choice of prime minister. Before the December elections, US and British officials were giving firm hints that they hoped Ibrahim Jaafari would be replaced by another Shia, Adel Abdel Mahdi, or if the secular parties did well, by the former prime minister Ayad Allawi.

Recently, US diplomats have been careful not to express any choices and there seems to be no truth in claims by Shia politicians this week that Bush sent a message to the leader of the Shia bloc via the US ambassador last Saturday saying he did not want Jaafari to be prime minister. US diplomats believe the story is being put out by Jaafari's rivals, who dare not break Shia unity and confront him personally but prefer to blame the Americans for allegedly exerting pressure while privately hoping the said pressure succeeds.

When these Byzantine games are over, and a new government is finally formed, the real difficulties will begin. For the new parliament to reach agreement and pass legislation on how to divide oil revenues, what power to allow the regions, and how to define the role of Islamic law will be even harder than choosing a prime minister. Confronting the militias and re-establishing order are titanic challenges. And all this will have to be done in the blinding heat of a summer in which people only have six hours of power to run their fans.

There is some comfort for Bush. Iraqi troops are gradually taking the lead in combined operations, as they did in Sunday's disputed mosque attack. This switch means that US deaths are down. Only 29 American soldiers have died so far this month, the second-lowest monthly total since the occupation began.

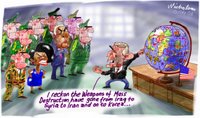

On Wednesday the US president proudly proclaimed: "Despite massive provocations, Iraq has not descended into civil war, most Iraqis have not turned to violence and the Iraqi security forces have not broken up into sectarian groups waging war against each other." Condoleezza Rice and Jack Straw will no doubt make similar points at their joint appearance in Blackburn today. When progress is defined in negatives, you have a measure of how bad the situation is.

The good news is only that things are not worse.

Sunday, April 2, 2006

a country scarred

Posted by audacious at 2.4.06

Subscribe to:

Post Comments

(Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment